Introduction

Much is said in scrutiny about the need to work from a clear evidence base, but what does that mean in practice? How can scrutineers know if evidence is to be relied upon and trusted or needs further qualification? What do scrutineers do if the information is partial, and how might they know that?

This practice guide will explore answers to these questions and develop practical approaches to applying evidence to policy development and better decision making.

What is evidence and why is it important for scrutiny?

Evidence, in any context, refers to the known or available information that people or organisations cite in support of their views, beliefs, decisions or recommendations. To gather evidence is to collect data. When deployed in support or rejection of a decision, direction of travel, argument or opinion data becomes ‘evidence’. This information can be objective, but more often than not in the world of scrutiny information is subjective, contextual and may be only part of the story.

Scrutiny needs to have a thorough understanding of issues that affect the council and the communities that people live in. To build this 360° view scrutiny should be asking for, developing and weighing evidence to inform recommendations.

In a purely academic study, we would start with a theory and a hypothesis (X happens because of Y) and we would design our research or data collection from this basis. In scrutiny issues are sought, selected and considered in much more dynamic ways (see Planning and Priority Setting – A Practice Guide – CFGS). Scrutiny may be presented with data and information first, and then invited to evaluate whether the right decision is going to be taken, or may be presented with a problem or challenge and must determine both how to consider the issue and what information is needed to support deliberations.

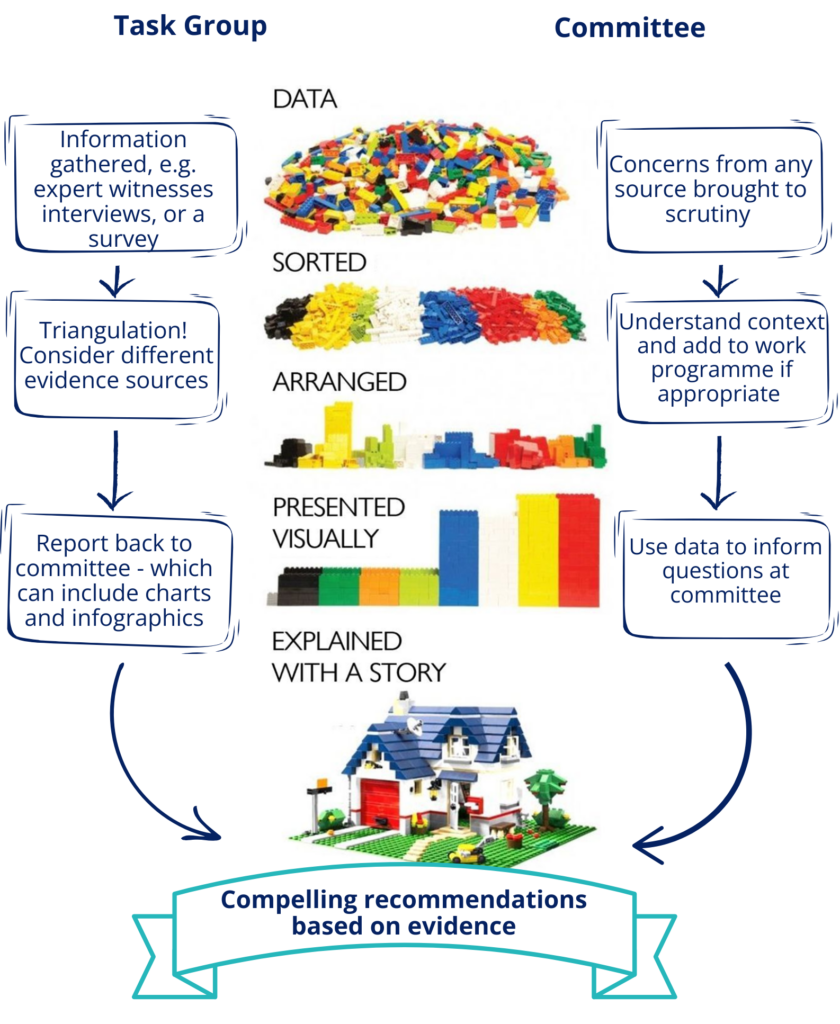

When starting to think about the role that data, information and evidence has in scrutiny, there are two distinct pathways which are important to consider. These are explored on the infographic below, which has taken the lego explainer ‘The difference between raw data and the stories data can tell’, developed by Andreas von der Heydt, and applied it to scrutiny.

The first pathway is often data, or information presented to scrutiny, usually at committee or in a briefing. The second is information sought or produced by scrutiny in task groups or similar. In both paths scrutiny will need to consider what story the data tells and evaluate which priorities to look at. For both we are looking to understand the complete story of service change, improvement or decision making.

Importance of evidence

Data and information are the currency of good scrutiny, understanding and navigating it is crucial to effecting change. A thorough evaluation of evidence will help to ensure transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making. Without evidence, scrutiny risks being opinion-based rather than fact-driven, reducing its ability to drive meaningful improvements and ensure public trust.

The main output of scrutiny, and its key lever to effect change, is recommendations. In order to make meaningful, useful recommendations it is necessary to undertake the thorough review, development, and analysis of evidence.

Where can scrutiny find information?

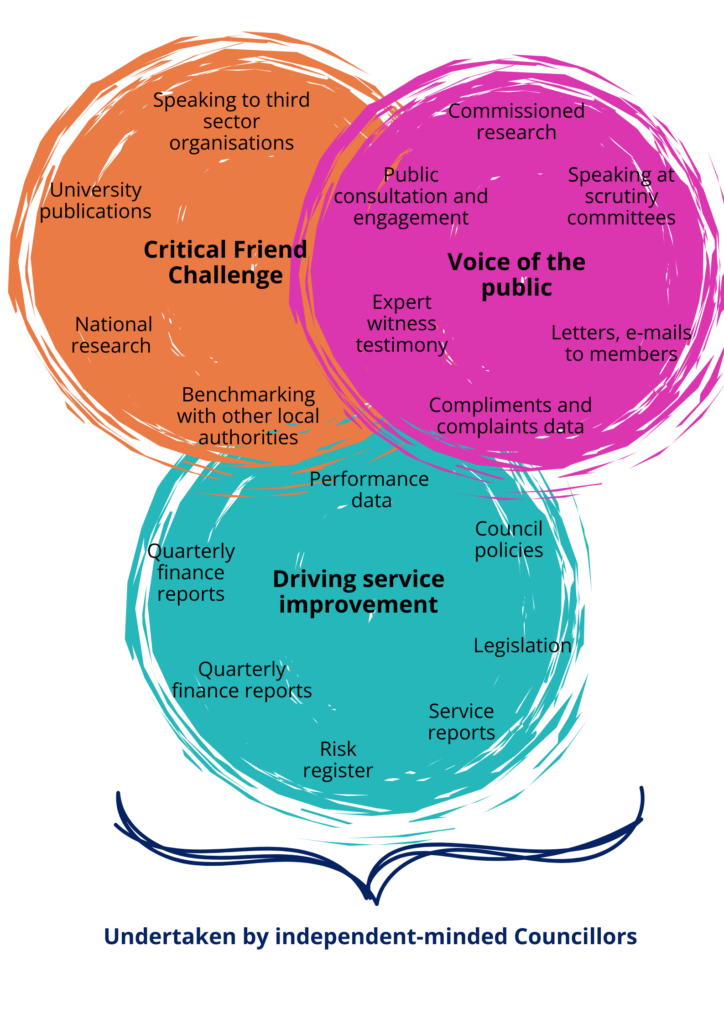

There are lots of rich sources of data and information open to scrutiny. Casting the net wide is useful to build the picture. The wealth of information that may come to scrutiny is suggested below, clustered around the CfGS four principles of good scrutiny. These are representative but not exhaustive of the sources of data that may come or be sought by scrutiny. It is useful to consider the types of data that might be associated with each principle. This can help ensure that scrutiny does not solely rely on limited data sources e.g. officers presenting from within the council. When considering requests for data, it is incumbent upon members to ensure that the pursuit of information is proportionate and relevant for the scrutiny function.

Amplifying the Voice of the Public

Collecting meaningful data should first start with engaging directly with residents and service users. Focus groups, workshops, and surveys can help gather insight. Community meetings and drop-in sessions allow for more open-ended discussions, capturing a broad range of perspectives. Scrutiny can also collect testimonials and case studies, encouraging people to share their experiences through written accounts, photos, or videos. Digital tools are increasingly valuable for data collection, with scrutiny committees using social media monitoring to track public sentiment, public idea generation platforms to crowdsource solutions, and interactive mapping tools to pinpoint community concerns or service gaps.

Driving Service Improvement

Data collection is key to identifying where services are working well and where they need improvement. Site or service visits provide first-hand observations, allowing councillors to speak directly to front-line staff and service users. Reviewing written and statistical evidence, such as performance reports, financial records, and policy documents, ensures scrutiny has a solid factual basis for its recommendations. Benchmarking against best practices allows scrutiny to compare data with other councils, helping to highlight strengths and expose weaknesses. Partnering with community organisations and influencers can also improve data collection, as these groups have access to local knowledge and can help gather qualitative insights from underrepresented voices.

Critical Friend Challenge

Scrutiny must ensure that data and evidence are robust enough to support strong decision-making. Facilitating expert discussions, such as roundtables or ‘spotlight reviews,’ allows for a deeper examination of policies and data sources, helping to validate findings. Engaging independent research bodies or consultants brings in objective analysis, ensuring that data is interpreted correctly. Benchmarking against other councils adds an external perspective, helping scrutiny committees challenge assumptions and push for higher standards based on comparative evidence. Scrutineers must also question how data is presented, ensuring that reports include necessary context, such as historical trends and comparisons to regional or national averages.

Undertaken by independent-minded Councillors

For scrutiny to be effective, councillors must take an independent and evidence-driven approach to collecting and analysing information, getting beyond politics. They should ask critical questions about data quality, collection methods, and gaps in the evidence. Councillors should also challenge whether data is presented in a way that supports good decision-making, ensuring that reports highlight key insights rather than just raw figures.

Drawing conclusions and triangulating information

It is useful to think of different types of data to support triangulation. Scrutineers do not need to be data experts, but they do need to be confident understanding and interrogating different types of information to build and understand the story told.

When triangulating data, it can help to build a picture using different evidence sources across different types of data. By way of example, a task group could take a mixture of national research already undertaken (secondary, quantative) with semi-structured interviews with expert witnesses (primary, qualitative) as well as council performance data (primary, quantitative). These different sources and different types of data can complement each other.

Quantitative data often focuses on the “what” of a problem, providing clear, measurable data that can track trends, identify patterns, and compare results over time. It allows for statistical analysis, making it easier to draw objective conclusions and support decision-making with hard evidence. Because it often involves large sample sizes, it can give a broad picture.

Qualitative research, in contrast, explores the “why” behind an issue, helping to understand people’s experiences, opinions, and motivations. It provides depth and context to data, allowing researchers to explore the reasons behind trends or unexpected findings. By using interviews, focus groups, and open-ended surveys, qualitative research captures the nuances that numbers alone might miss.

A key benefit of qualitative research is its ability to uncover new insights. When people are given the chance to speak openly, they may highlight issues or solutions that hadn’t been considered before. This makes qualitative methods particularly valuable for exploring complex social issues or understanding the impact of policies on different communities.

By way of an example, a hospital trust gave patients the option to choose to have the same operation at two different hospitals across the area. When they looked at the statistics the scrutiny committee could not understand why much larger numbers of patients were choosing to attend one hospital and not the other. The waiting times were higher at one hospital, and still patients were opting to have their operations at that hospital. The qualitative data did not explain what was happening. It was only when focus groups were held with patients that the reasons which underpinned choice came to light: one hospital had an under cover bus station and as a result, those patients that got public transport all chose one hospital over the other, even if they had to wait longer.

How do I approach the data presented to scrutiny?

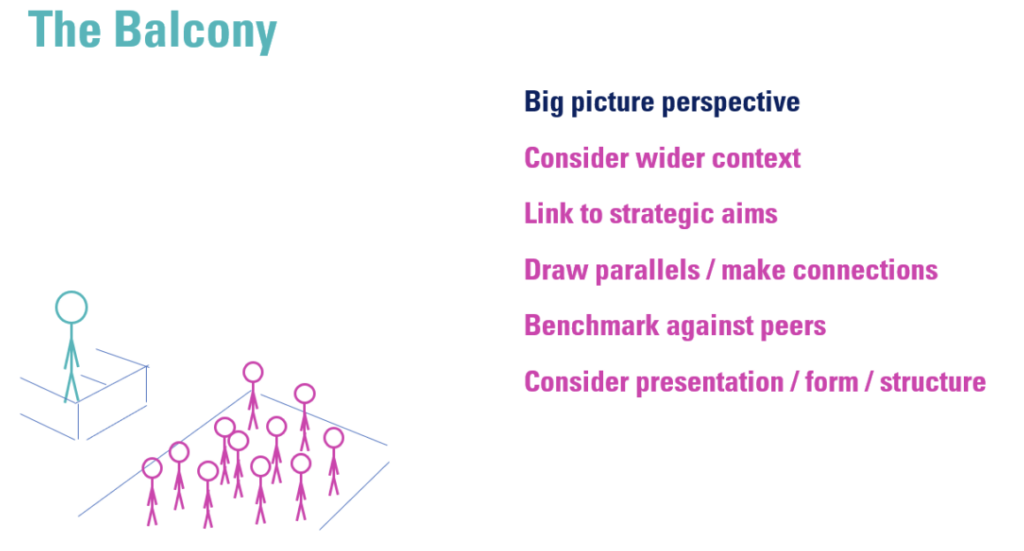

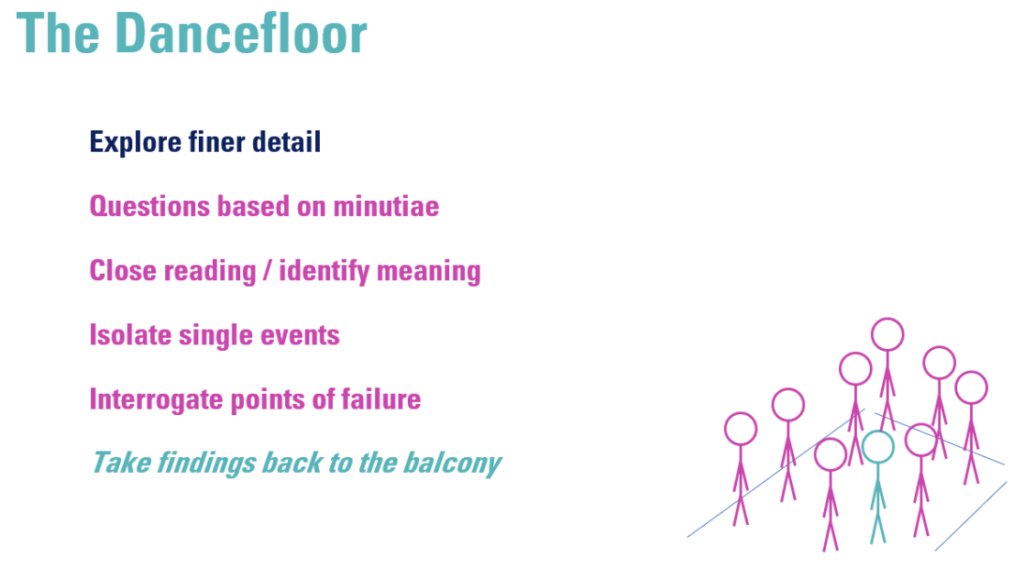

A good analogy to explore about perspectives from which to interrogate data and information at scrutiny is the balcony/dancefloor, which is similar to the zoom in/zoom out approach.

Imagine being at a crowded disco

From the balcony, you get a broad view of the whole room. You can see how busy it is, spot trends, and get a sense of the overall atmosphere. In scrutiny, this means stepping back to assess the big picture, looking at how different pieces of data fit together and whether they support wider strategic goals.

On the dancefloor, you’re in the thick of things. You can see individual dancers, notice specific moves, and pay attention to the details you wouldn’t pick up from above. In scrutiny, this means digging into the detail, questioning specific figures, and challenging whether the data has been presented in a way that tells the whole story.

The strategic perspective looks at data in the context of past performance, future targets, and how it compares to similar councils or national trends. This helps scrutiny to understand where the organisation stands and whether performance is improving or declining.

The detailed perspective digs into the specifics of the data, questioning what it does or doesn’t tell us. This involves looking for gaps, inconsistencies, or hidden trends that might not be obvious at first glance.

Effective scrutiny isn’t about choosing one perspective over the other, it’s about consciously applying both, and knowing which approach to use when. Strategic questions should be shaped by detailed investigation, and detailed questions should be guided by an understanding of the bigger picture. By moving between these perspectives, scrutineers can ensure they are both challenging the data effectively and drawing meaningful conclusions that lead to better decision-making.

Using evidence to drive improvement

Scrutiny plays an important role in shaping the direction of the local authority. It is there to consider strategies and policies and to make recommendations for improvement. All the information presented to scrutiny committee or briefings will be based on some form of data – and part of the role of scrutineers is to ask if the evidence fully substantiates the decisions, policy direction or strategic development. To do this properly, scrutiny councillors should feel empowered in how they engage with information and data.

Scrutiny can play a key role in bringing innovation to a local authority by learning from the experiences of other councils. By looking at how similar challenges have been tackled elsewhere, scrutiny can identify new approaches, test fresh ideas, and push for better ways of working.

One way to do this is through benchmarking, comparing local performance against similar councils to identify where improvements could be made. If another authority has significantly lower staff absence rates, for example, scrutiny can investigate how they achieved this and whether similar strategies could be applied locally. This ensures that scrutiny is not only holding the council to account but also encouraging it to adopt better ways of working.

Another useful approach is reviewing case studies and best practices from other councils. Many authorities publish reports on successful projects or policy changes, which scrutiny committees can use to explore new ways of tackling local challenges. Instead of reinventing the wheel, scrutiny can recommend solutions that are already proven to work elsewhere.

Engaging with scrutiny members from other councils can also provide valuable insights. Through networks, shared meetings, and conferences, scrutiny committees can learn from others who have successfully influenced policy change. This collaboration helps develop more effective scrutiny methods and encourages local authorities to take a fresh approach to problem-solving.

Inviting external witnesses to scrutiny meetings, for example, councillors, officers, or experts from other councils, can help introduce new perspectives and challenge existing thinking. If a neighbouring authority has successfully implemented digital transformation, for instance, hearing directly from those involved can provide practical insights into how the process worked and what lessons were learned.

To ensure innovation is both practical and effective, scrutiny can also encourage the council to pilot new ideas before fully implementing them. Testing a successful policy on a small scale first allows for low-risk experimentation and helps adapt ideas to fit local needs. This makes it easier to implement change without unnecessary risk or disruption.

How to make evidence work for you – a checklist

Use these questions to ensure that you are in the best position to use and challenge evidence effectively during scrutiny:

1. Does this format work for me?

Councillors have the right to request information in a format that is clear and accessible. If a presentation or report isn’t working for you, say so. It’s better to ask for information to be explained in a different format than to waste time struggling with something unclear. If you’re finding it difficult to understand, chances are someone else is too. By speaking up, you help others who may feel the same way but hesitate to say so. It will be most useful if this is done in good time as part of work programming.

This may include:

- Choosing between written reports, presentations, or verbal briefings.

- Seeking ways outside committee meetings to gain greater understanding.

- Requesting concise presentations to allow more time for questioning.

- Challenging unclear report layouts or requesting summaries.

- Asking for benchmarking or comparative data to provide context.

2. Is scrutiny getting the information it needs to do its job?

Scrutiny is only as effective or persuasive as the information and evidence that it is making recommendations from:

- Has the evidence provided answered key questions, or does it raise new ones?

- Are there gaps that require follow-up reports, witness sessions, or further research?

- Does the committee need to cite legal powers in order to access data?

3. Is the evidence behind the claim verbal or published?

When receiving presentations, ensure that claims are supported by a clear evidence base and that scrutiny has seen that evidence to give assurance.

- Are conclusions backed by published data or research?

- Can the committee access the full evidence base, rather than just a summary?

- Would additional documents or data sources provide better transparency?

- How up to date is the data that conclusions are based upon?

4. Is this evidence objective and reliable?

Scrutiny should challenge potential bias and weak evidence:

- Who produced the evidence, and could they have a vested interest?

- Has the data been peer-reviewed or validated by an independent source?

- Are conclusions based on robust analysis, or are assumptions being made? Are they reasonable assumptions?

5. Can I influence how data is collected?

If the council is collecting primary data (e.g., surveys, consultations), consider:

- Are the questions asked fair, unbiased, and relevant.

- If the method of public engagement ensures a representative response.

- Whether the sample size is large and diverse enough to draw meaningful conclusions.

6. Are we hearing from the right people?

The credibility and diversity of witnesses matter:

- Are key stakeholders (e.g., residents, service users, frontline staff) being consulted?

- Is expert testimony being sought where relevant?

- Are alternative viewpoints being considered, rather than just official council reports?

7. Can I put this data into regional, national, and other contexts?

Understanding how local data compares to wider trends is helpful to develop alternative approaches:

- How does our council’s performance compare to similar or neighbouring authorities?

- Are there relevant national statistics or best practices we can learn from?

- Would additional benchmarking data help put findings into perspective?

8. Could different forms of evidence strengthen our findings?

A variety of evidence types can provide a more complete picture:

- Can the committee use triangulation (e.g., combining statistics, expert views, and public feedback) to validate findings?

- Are there case studies, lived experiences, or site visits that could add context?

- Would additional qualitative or quantitative data help confirm conclusions?

9. Are scrutiny recommendations practical and evidence-based?

Once scrutiny has gathered evidence, its recommendations must be clear and actionable:

- Do proposals align with what the evidence suggests?

- Are recommendations realistic and achievable within council resources, and how might their achievement be measured?

- Have potential risks and unintended consequences been considered?

10. Are scrutiny recommendations practical and evidence-based?

Ensuring scrutiny has an impact requires tracking progress:

- Are there mechanisms to review whether recommendations are implemented?

- Can scrutiny request updates or progress reports from relevant departments?

- Should an issue be revisited in future work programmes to measure long-term impact?

All resources

All resources